Quiet Quitting– and more leadership malarkey

Okay, let’s get this out of the way: this “Quiet Quitting” stuff is just a load of crap. Nothing more.

Don’t fall for it, thinking you now have some incredibly useful excuse for why people aren’t performing as you think they should. Sorry – no cigar.

It’s a made-up phrase to describe an age-old problem. Likely invented by some consultant or academic trying to sell you something. (wasn’t me, promise)

First, employees playing hide and seek with their efforts and attention is nothing new. It’s likely gone on since we had employers and employees.

When I was in the USAF, we had a phrase we would use with people, especially as they were nearing a change in station, or were nearing their separation or retirement. We called it ROAD – Retired On Active Duty.

In other words, they had quit working for the most part, and doing just enough to make sure they didn’t get whacked.

Now we say, “he quit some time ago, just hasn’t stopped getting paid.”

This didn’t begin in 2022, so don’t pretend like it’s this newfangled, pandemic-apocalypse-WFH-related shenanigan.

if you’re just now hearing about stuff like this. Well, that’s on you. You’re likely easily bamboozled and equally confused.

Next, that whole “do more than required” has a name. It’s called discretionary effort.

Discretionary effort is that effort exerted or offered by the employee, beyond that which is required to keep their job.

Discretionary effort. I refer to it as the holy grail of leadership. You know you’re doing something right when those whom you lead offer you this added degree of ownership and effort. (Bad news – if you aren’t getting discretionary effort, well, that’s on you too!).

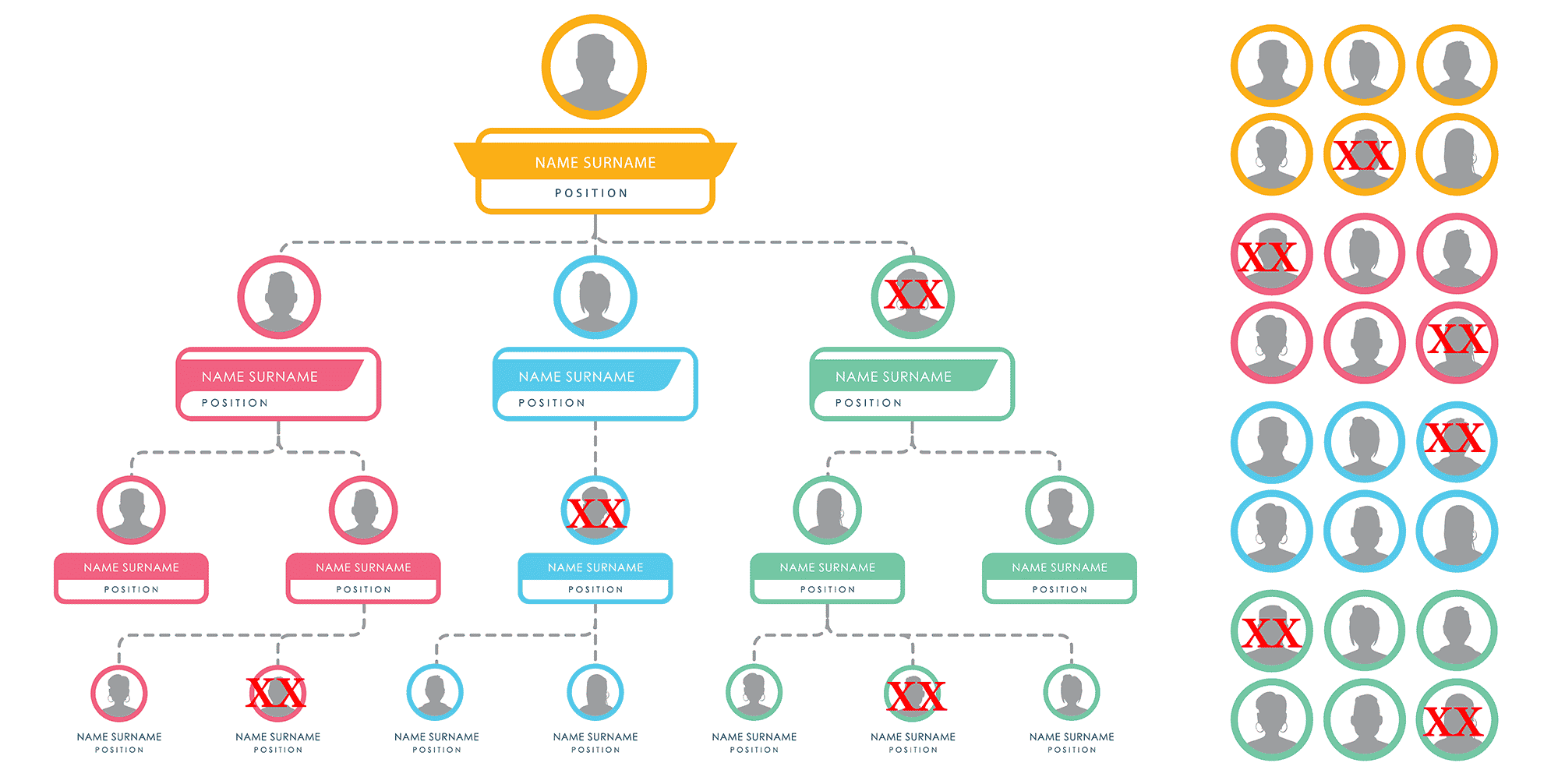

Here’s the rub; since we’re so incredibly bad (global leadership) at setting clear expectations, including written job descriptions, we may not realize… do you know what you call an employee who gives you no discretionary effort, only doing what is specifically required by the organization?

That’s right, a fully satisfactory performer. A 2 out of a 3-point scale, or 3 out of 5.

You set the requirements. You set the expectations. You set the minimum qualifications.

And they did exactly as you asked.

So don’t act like they’re doing less than is necessary, or less than what we actually required, because it’s neither of those. In fact, it’s exactly what we asked for.

The reality is that we aren’t very good at setting clear expectations for others, so our expectation has become that employees would always “do the right thing,” even if we weren’t clear on what that right thing is. Even if we didn’t know what it was at the outset.

So don’t blame the employee for “just doing their job.”

If you insist they do something, spell it out. Put it in English. Then manage to those expectations.

Wait a minute… that sounds eerily like typical performance management.

Finally discretionary effort is given in only three circumstances, reasons or events:

- The employee is hardwired to do it. Some folks just can’t help themselves and will do a little bit more than expected of them regardless of their environment or for whom they work. They do it because that’s what they need personally to be satisfied when they go home at night.

The upside is, even with crappy leadership, you get the extra, discretionary effort from the hardwired crew. The bad news is, when they decide that that discretionary effort is not valued appropriately, they don’t just lower their effort.

No, they leave.

- Leadership trust. People will give us the discretionary effort if they trust that will do good things with it; they have to believe that that we won’t abuse the added input, nor them for providing it.In other words, they want to make sure that they can trust us to not take advantage of them, or take them for granted.

- Leadership influence – our ability to help people understand our vision, know the value of helping us pursue that vision, and then personally want to be part of wherever it is that were headed.This leadership influence is critical to the discretionary effort equation.

So, to put a bow on it: if we hire the right person (#1 above), and we provide a reasonably successful vision to follow, and are capable of positively influencing others to go with us on our journey, the odds are stacked in our favor that we’ll get that coveted discretionary effort.

If not, we can always just blame it on the Quiet Quitting, or Great Resignation, or some other made-up fad of the day to excuse our own lack of discretionary effort.

Oops, did I say that out loud?

Remember, Grace and Accountability can coexist.